Rage is a particularly powerful emotion that can both be very effective and ineffective at eliciting change. Who ever experienced a good row with their spouse or parents and felt the relief and new understanding afterwards can testify to the effectiveness. Whoever was stonewalled by the other party can testify to the ineffectiveness.

The rage of age

During my PhD-years, we, a young fellow postdoc and I, were called the 'angry young men'. In 2012, we were already very concerned about the state of the planet and the apparent ineffectiveness of science to change the hearts and minds of policymakers, industry and the general public. We felt like a niche activity and it was quite depressing to see that in a prime ecological research institute there wasn't much willingness to really engage with society on these all-important topics. Many took a cynical stance, arguing that events could not be turned for the better and that nature was in effect lost. But cynicism takes you exactly there where you do not want to be, it resigns you to that unhappy fate, because it justifies your own inaction. Its paralysis.

We were told by senior staff that we had to learn to be patient, that it took 20 years for a scientific insight to make it to the policy arena and this infuriated us. It still does, realising that so much is at stake. In this perspective we were quite proud to be called the angry young men, as it suggested activity in an environment that in a way had gone stale, an organisation that was busy window-dressing its impact on the world. In fact, in the meantime, the only things that have changed for me is that I am not that young anymore (next year 40....) and that I feel more hopeful given all kinds of initiatives sprouting up (for instance this and this).

But I still feel angry regularly. For older people, particularly men, one sometimes speaks of the rage of age. It is the fire ignited by their own approaching death that gives these persons a particular power to motivate change in others. At the midpoint of my life (roughly), I think I feel the rage of age already now. I can only hope it will be as effective as in more experienced people.

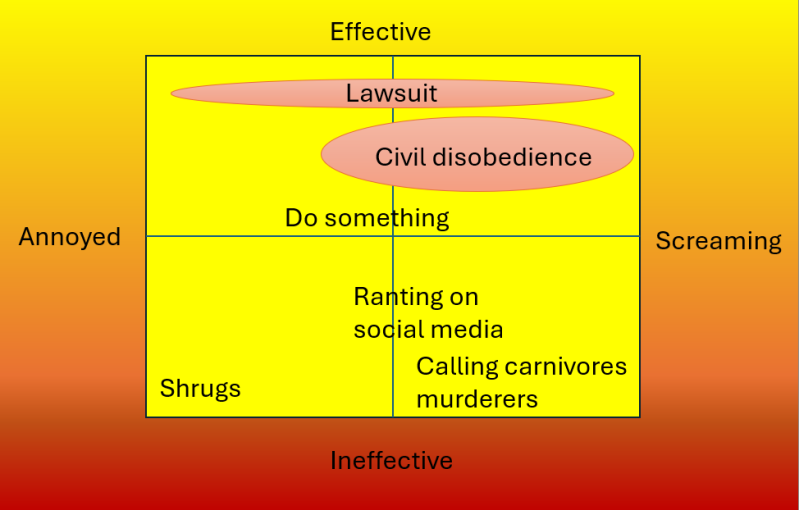

But, let's look at some of the more effective and ineffective ways of being enraged. The flavours of rage.

If you get to this point, you probably should have expressed your anger sooner...

Source: here.

The flavours of rage.

Do something

Also in my PhD years, a small group of us felt we had to 'do something'. To put cynicism aside, and act. Quite randomly my fellow young angry man proposed we should plant a food forest at the NIOO, our workplace, to show that alternative modes of farming are possible. We enthused our director and with a small budget planted a miniature food forest, that is showcased during the regular guided tours through the institute's building. I like to believe this small agroforestry plot inspired others. For sure it led to a very nice PhD project studying how food forestry affects belowground biodiversity and functioning (including carbon storage) compared to other types of land use (e.g., arable farming, grassland). A seed was planted.

Rant on the internet

Another colleague, whom I respect deeply for their wide and deep knowledge of natural history and the impact of climate change on the biosphere, can often be found online. They take pride in the online battles they are waging against climate change deniers, trying to debunk their faulty claims. I think this is courageous, and I admire their preserverance, energy and motivation. But I cannot help wondering, does it work? Are they changing the hearts and minds of these climate change deniers? I know the activity comes at a personal cost, is it worth it? (I am ranting too btw.... is that working?)

See you in court

Much more effective are the recent sweep of lawsuits launched by environmental NGOs. The first succesful case was the lawsuit filed by Urgenda against the Dutch state, in 2013. Headed by lawyer Rogier Cox, the NGO claimed the state was not meeting a minimum carbon dioxide emission-reduction goal, established by scientists, to avert harmful climate change and was endangering the human rights of Dutch citizens as set by national and European Union laws. In 2011, Cox wrote a book, Revolution Justified, where he discribes how the climate crises can be addressed through the law and lawsuits and he decided to do just that in the following years. After a long litigation process the Dutch Supreme Court ruled that the government needs to meet an emissions goal of 25% reduction from 1990 levels. The Dutch government then began enacting measures to meet the emissions target. Already planning on banning coal power plants by 2030, the government ordered the shutdown of the Hemweg plant in 2020. The Dutch government passed a new climate plan in June 2019, targeting 49% carbon dioxide emissions reduction by 2030. This plan includes taxes on industries on carbon dioxide emissions, transiting from gas to electric power through incentives, and pay-per-use driving taxes as early as 2025.

With the newly enacted government, I wonder how these plans are doing now. Meanwhile, Cox successfully repeated his strategy against the Belgian state and Royal Dutch Shell. Today, a new lawsuit is afoot against the ING Bank, you can still file as a plaintiff together with >21.000 others (and me)....

Non-violent civil disobidience

In 1930, 79 volunteers marched 388 kilometers from Ahmedabad to Dandi, India, to make salt, thus defying the British salt tax. Thousands more had joined the group upon arrival in Dandi. The march was led by Mahatma Gandhi. Gandhi opposed the imperialist system of progressive exploitation and ruinously expensive military and civil administration, which reduced the people politically to serfdom. Using non-violent protest and actively disobeying the law, Indian independence was finally won in 1947.

Civil disobedience is a potent way of protest, known to be able to change the world. Scientist are not typically associated with lawbreaking, but a movement is now afoot, arguing that the present climate crisis warrants civil disobedience by scientists. As scientist we know the most about the state of the planet and its climate. We know that billions will suffer when we move from 1.5 °C to 2.0 °C global warming. We've hit the 1.5 °C mark earlier in the year, and it looks like we will permanently overshoot 1.5 °C in the coming years. This knowledge creates a moral obligation. An obligation to act in defence of human rights. Or, as they say in the Scientists Rebellion, "The privilege to know, the duty to act".

The trusted position of scientists in society affords a respected standpoint from which to demand change. The credibility of scientists is influenced by whether they are seen to be acting in line with shared values and promoting the well-being of others and, in the context of climate change, according to whether their actions clearly align with their message. As an ‘ethical crisis’, the climate emergency warrants civil disobedience under certain specific conditions. These include that fundamental rights to life and well-being are being undermined in an unjust manner; that the action has the potential to be effective and avoids harm; and that such action is undertaken as a last resort, other avenues having been pursued. Civil disobedience is justified in the context of a broader ‘fidelity to law’ that contests specific policies or practices but not the legitimacy of the state in general terms. So it is not anarchism.

Often, the legitimacy of scientists is said to rest on their status as impartial, objective or ‘neutral’ observers, and the idea that science and politics should remain separate (they are not!). Moreover, no dialogue between science and society can ever be value neutral, and it should not aim to be. The widespread notion that sober presentation of evidence by an ‘honest broker’ to those with power will accomplish the best interests of populations is itself not a neutral perspective on the world; it is instead conveniently unthreatening to the status quo and often rather naive. In general, studies have found the credibility of scientists is not undermined by advocacy; on the contrary, many members of the public expect scientists to use their knowledge to advocate for the public good! Civil disobedience is an efffective short term strategy, but it needs to be complemented with other long-term strategies.

It is important to be clear that the personal risks associated with civil disobedience vary dramatically with people’s circumstances. We recognise that there are many frontline activists who have lost their lives protesting and resisting in defence of people and planet. To be able to engage in disruptive protest in relative safety is a privilege held by citizens living in comparatively liberal societies.

Leading this effort are the people with the Scientist Rebellion, the science equivalent of Extinction Rebellion. Will you join ?

My scientific 'comming out'.

Scientist rebels blockading the A12 highway in the Hague, the Netherlands.

14 Sept 2024.

Add comment

Comments